- Home

- Christopher Kemp

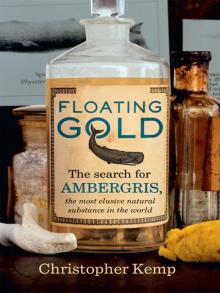

Floating Gold

Floating Gold Read online

Dedication

For

EMELINE, MAX, & IZZY,

my fellow ambergris hunters.

This is a record of the time.

In Memory of

DR ROBERT CLARKE

(1919–2011)

Epigraph

Who would think, then, that such fine ladies and gentlemen should regale themselves with an essence found in the inglorious bowels of a sick whale! Yet so it is. * HERMAN MELVILLE, Moby-Dick (1851)

An ignorant Fellow in Jamaica, about two Years ago, found 150 Pound Weight of Ambergreece dash’d on the shoar, at a Place in these parts called Ambergreece Point, where the Spaniards come usually once a Year to look for it. This vast Quantity was divided into two Parts; supposed by Rolling and Tumbling in the Sea. This Man tells me that ’tis produced from a Creature, as Honey or Silk. And I saw in sundry places of this Body, the Beaks, Wings, and part of the Body of the Creature, which I preserved some Time by me. He adds, That he has seen the Creatures alive, and believes they swarm as Bees, on the Sea shore, or in the Sea. * Philosophical Transactions and Collections, to the End of the Year, 1700

Contents

Cover

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: Wellington, 2008

Introduction: Marginalia

1 On Long Beach

2 There Is a Piece at Rome as Big as a Man’s Head

3 The Beach Mafia

4 It Looked like Roquefort and It Smelled like Limburger

5 A Molecule Here and a Molecule There

6 Close Encounters of the Ambergris Kind

7 The Hopefuls

8 On the Road

9 Gone A-whaling

10 A Meeting

Epilogue

Picture Section

About the Author

Copyright

Dear Dr. Clarke,

I did have another question for you. I’ve always pronounced ambergris without the “s” at the end, like the French from which the name is derived. Like this: ambergree. Others I’ve spoken with have pronounced the “s,” but softly, like this: ambergrizz. How do you pronounce it?

All the very best!

ck

Dear Mr. Kemp,

Like all those with whom I have spoken about ambergris I pronounce the word like this: ambergreez, and I recommend that you do the same. After all, you are not French, are you?

Yours,

Robert

PROLOGUE: WELLINGTON, 2008

On Saturday, September 20, 2008, the excitement was beginning to grow on Breaker Bay, near Wellington, New Zealand. Although it was early spring and still cool, a crowd had gathered to investigate a strange object that had washed ashore during the night. It was large, perhaps the size of a 44-gallon drum, and weighed an estimated 450 kilograms or more. No one had seen it arrive. It was just there on the sand. Roughly cylindrical in shape, it was the colour of dirty week-old snow.

On the following Monday, national news media were beginning to report the arrival of the object on the beach. To the people who live in the Wellington suburbs near Breaker Bay, the news reports were hopelessly late in coming. Everyone already knew about the object. It had been sitting incongruously on the beach for the last two days. Hundreds of people had already wandered over to take a look at it. Seagulls had been pecking at it as it slowly settled into the sand. Rumours spread quickly through the coastal communities around the bay. It was, one of the prevailing opinions stated, a large piece of cheese. In fact, people said, it was probably Brie. It must have been dumped on the beach by the notoriously rough waters of Cook Strait — a large cylinder of soft cheese swept toward the bay from the busy shipping lanes.

Perhaps, some people suggested, it was industrial soap. Others asked: Could it be some kind of meteorite?

And then the situation became stranger still. People were now taking pieces of the object, carving off large heavy servings of it with whatever tools they could find. They then took their samples home, protecting them from decomposition and through the further attention of curious seagulls.

At night I watched the news reports with growing amazement. What would make people act this way? Six months earlier, my wife and I had moved from the United States to Dunedin, a midsize coastal city that sits near the southernmost tip of New Zealand’s remote and rain-swept South Island. I was working as a biologist at the University of Otago, a large research institution in the city, and so was my wife. As relative strangers, we wondered aloud to each other if this behaviour was particular to New Zealand. Perhaps it’s an aspect of the national character, we said, to act this way when something unusual washes ashore.

But another rumour had begun to circulate: the mysterious object was ambergris.

“I’m pretty sure this is ambergris,” Geraldine Malloy told a television news reporter breathlessly. “I think it’s the find of a lifetime. I’ve been looking for it for a long time.” She was standing over the object, wearing an anorak and using a long-handled spade to break off smaller pieces from the whole.

Before September 2008, I had never even heard of ambergris before. Now I sat transfixed, as people almost rioted on the beach, armed with garden tools, trying to obtain just a small piece of it. It was one of the strangest sights I had ever witnessed, and I was determined to learn more. I discovered that ambergris is excreted only by sperm whales, and it is rare and extremely valuable. In fact, ambergris is valuable enough that rushing to Breaker Bay armed with a long-handled spade to break off some smaller pieces from the whole was a reasonable investment of Malloy’s time. Used as an ingredient in the manufacture of perfume — and for more esoteric purposes in more distant places — ambergris is traded on the open market for up to $20* per gram, depending on its quality. As a useful reference, gold is currently trading at around $30 per gram. Unlike gold, people occasionally report finding ambergris on remote beaches in lumps that weigh more than 20 kilograms — or $500,000 worth. And at $20 per gram, the object being enthusiastically divided up by the crowd at Breaker Bay was worth around $10 million.

Ambergris becomes more valuable as it ages. A well-aged piece of ambergris is unusual, and the arrival of a well-aged piece the size of the strange object on Breaker Bay was a singular event. It would have been comparable to finding a lump of gold the size of a suitcase in the middle of a well-traveled path. No one on the beach seemed certain that the object was ambergris, but no one was taking any chances that it wasn’t, either. The crowd grew larger. People arrived with bedsheets, which they used as makeshift slings to transport bowling ball – size pieces of the object home. Those managing to secure even a handful — a greasy wet piece weighing maybe half a kilogram or so — were potentially taking home $5,000 worth of ambergris.

The excitement continued to grow throughout the day. “So many people have rung in saying, ‘It’s worth half a million dollars,’” Wellington City Council spokesman Richard MacLean told the New Zealand Herald. “We feel honour-bound to actually go out and stake our claim on it.”

And then on Tuesday morning — just three days after its arrival — no sign remained to prove that the object was ever there. The crowd had removed it, piece by piece and kilogram by kilogram, with their spades, bags, and improvised slings. All around Breaker Bay and farther afield, in suburbs across the city, people were celebrating their sudden and unanticipated wealth.

There was only one problem. It wasn’t ambergris, says Nic Conland, the Environmental Protection team leader for the Greater Wellington Regional Council. It was a large seaborne block of tallow. “Essentially, it’s lard,” Conland told me a few months later by telephone. “We’re not sure, but it looked like it had been part of a drum that had fallen off a ship.”

Pieces of it had started to ap

pear for auction on online trading sites, listed as ambergris. But it was worthless. It was worse than worthless — it was a potentially harmful pollutant. It could clog every kitchen sink in the Greater Wellington metropolitan area. And its provenance was, for the most part, still unknown. On Wednesday — four days after the object had washed ashore — the Greater Wellington Regional Council finally broke its silence, posting an update for the public on its website. It read: “Wellingtonians who earlier this week removed several hundred kilograms of lard from the beach at Breaker Bay are urged to make sure that they dispose of it thoughtfully once they realize that it is not ambergris and therefore largely worthless.”

Lard. Largely worthless. The story, for so many, had ended.

For me, it had only just begun.

INTRODUCTION:

MARGINALIA

In the course of writing this book, I was asked one simple question again and again: why ambergris? What was it about the substance, which Franz Xavier Schwediawer had called, in 1783, “preternaturally hardened whale dung”, that made me want to trudge month after month along lonely windswept coastlines? Sometimes, especially on wet blustery days, even I struggled to find an answer.

In the beginning, the value of ambergris was as good a reason to go looking for it as any. I was drawn to the idea that I might find something worth $50,000 on the beach, just dumped there, glistening on the high-tide line. For months, this was enough to send me out to the coast. The fact that ambergris looks like an unremarkable piece of driftwood and requires decades at sea to transform just added to its appeal.

But time passed and my motivations evolved.

When I was a child, I was fascinated by the natural world. My parents fed my interest, buying me books filled with photos of animals. I took them on family vacations with me, so that I could study them during long car journeys, tracing a finger over the giant squid and the Amazonian anacondas. But the most worn and dog-eared pages were always those with the photos of the oddest and most otherworldly animals on them: deep-sea angler fish, duck-billed platypuses, and bird-eating spiders. The marginalia. More than anything else, I was attracted to their strangeness. Years later, on long walks in the English countryside, I collected skulls and brought them home, cleaning them in my bedroom and lining them up alongside one another like trophies: rabbits and squirrels, with their curving yellow incisors; a crow skull, with its sturdy black beak and a brain case as thin and fragile as a ping-pong ball.

I can still remember finding a fragment of bone buried deep in the soil in my backyard when I was twelve years old. I sent it to scientists at the nearby Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, with an accompanying letter asking them to identify it for me. And they did. It was the parietal bone of a fox skull. The reply came with an invitation to visit the museum to see how its scientists prepared specimens for display.

All day my mother and I walked from room to cluttered room, into parts of the museum that were not open to the public. We had passed beyond an invisible barrier, permitted entry to a special exclusive realm. We saw shelves lined with dusty fossil fragments and glass jars filled with enormous preserved insect specimens. At one point I clambered up a stepladder to peer into a bubbling vat of chemicals. Inside, several fox carcasses were undergoing a process to strip the flesh from their bones. As I watched, a technician leaned over the side and used a tool to probe the liquid, hooking a carcass and hauling it to the surface for me to see. My mother — who did not need to see decomposing fox carcasses as badly as I did — nevertheless spent several minutes gently convincing the technicians that it was appropriate to show them to me. And so I stood at the top of the ladder, breathing the warm fumes, looking at the white glistening bones.

It wasn’t enough just to visit the museum. I needed to tiptoe through the unvisited parts as well, through the unexamined marginalia not on display. It was a glimpse into a world behind a world.

A decade later, I earned a degree in biology; later still, a master’s degree in epidemiology. And I embarked on a career in molecular biology and neuroscience. My fascination with the natural world has never left me.

As a scientist, I’m used to being able to access information when I want it. From my desk, I can download millions of scientific articles with the click of a mouse. Within a minute or so, I can know the exact three-dimensional structure of a protein I am studying, or the genetic code that made it.

When I first heard about the mysterious object on Breaker Bay in September 2008, I went online immediately, thinking I’d learn everything I needed to know about ambergris in a few minutes. But I failed. In fact, to begin with I found almost no useful information at all — just a handful of esoteric scientific papers and medical textbooks, most of them published in the eighteenth century. They were full of contradictions and inconsistencies. There are, of course, more recent news articles that mention ambergris, which tend to appear after someone has stumbled over a lump of ambergris on a remote beach somewhere. At least half of these news stories refer to ambergris as whale vomit — a persistent description which suggests journalists are not taking their work seriously. They conjure headlines like “WHALE COUGHS UP A JACKPOT”— an article from the New Zealand Herald in 2006. A few of the more complete whaling histories include brief sections on ambergris — notably The Natural History of the Sperm Whale by Thomas Beale (1839), Whales and Modern Whaling by James Travis Jenkins (1932), and most recently Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America, by Eric Jay Dolin (2007). But mostly, it is marginalia.

It wasn’t always the case. In 1794, when Henry Barham wrote Hortus Americanus, exclaiming that ambergris was “a universal cordial”, it was one of the most widely used substances in the world. But that was 1794. Apart from a few traders and perfumers and a handful of fortunate beachcombers, the world seems to have forgotten about ambergris. For a few weeks toward the end of 2008, I had almost forgotten about it too. I’d managed to put it out of my mind. My wife had just given birth to our son. We were sleep-deprived and busy. Whenever we could, though, we drove along the winding harbour road, past clumps of flax and cabbage trees, to walk the shoreline of the local beaches.

I would follow the high-tide line — a long, irregular wet trail — pushing my son’s stroller across the beach, collecting objects from the sand. Just like when I was a child, I was less interested in the easily identified substances — the tapered green fronds of bladder kelp and the empty mussel shells. Instead, I was drawn to the strange and unidentifiable, collecting odd and misshapen items that might have come from the other side of the world.

Gradually, I began to think of ambergris again. I started to search for it along the shoreline. And soon enough, I was calling museum curators in London and tracking down international ambergris traders. It was as if I had fallen down a rabbit hole. More than anything else, my motivation was the complete lack of reliable information. I could no longer stand not knowing. The scientist within, the part that searches for clarity, wouldn’t let me rest until I had discovered the truth. Even the descriptions of the characteristic odour of ambergris seemed inadequate. Surely, I reasoned, it was simply that no one had tried hard enough yet to describe it. Eventually, it became more than I could bear. I decided to do everything possible to experience and describe ambergris properly. What was the point, after all, of reading about the unmistakable odour of ambergris if I could not then smell it for myself?

As a result, I spent two years exploring some of the strangest marginalia I had ever come across. In the process, once again, I walked through the unvisited and forgotten corners of familiar places, and glimpsed secret worlds. I was driven by the same irresistible impulses I’d had as a twelve-year-old child. I wanted, in other words, to experience something more fully and completely than anyone else. And the need to do so took me across the world, in search of floating gold.

1 ON LONG BEACH

Ambergris is an extraneous Substance, that swims in the Sea, and is swallowed as a Delicacy by the Fishes, and voided by them again un

digested. It seldom stays long enough, to be found in their Bodies.

* CASPAR NEUMANN, “On Ambergris” (1729)

I tell people that they’ve got to sniff a lot of dog droppings before they find a bit of ambergris.

* Interview with amateur historian LLOYD ESLER, New Zealand (2010)

It’s a rainy afternoon on Long Beach. I am standing beneath a mackerel sky, holding a strange little object in my hand. It’s a pale green-grey colour, like a barely steeped cup of green tea, and it looks like a potato. I hold it up to the grey light and examine it more closely in the rain. Sitting in the palm of my hand, it feels light and spongy. It could be a thick stalk of decomposing seaweed, still wet from the ocean, or an old and waterlogged piece of driftwood. It might be a shrivelled piece of marine sponge, dislodged from the seafloor and then washed ashore by the last tide. It could be an almost infinite number of different things. In fact, the object in my hand could actually be a potato. It might have traveled from the other side of the world, bobbing and rolling around on ocean currents for months, or even years, before finally arriving on the beach. I bring it to my nose and carefully smell it, hoping it is ambergris. Nothing. It has no detectable odour, except perhaps the faintest briny trace of the sea. And so I discard it and move on again, slowly making my way northward along the beach. Head lowered, I survey the wet sand, bending occasionally to pick up an object before smelling it and then pitching it over my shoulder. Behind me, I have left a wide and messy field of debris.

Floating Gold

Floating Gold